Stereotypes were Made to be Broken: Hedy Lamarr

- U of T Scientista

- Oct 23, 2018

- 2 min read

Hedy Lamarr, born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria, first graced the Silver Screen at the tender age of 17. After gripping the attentions of Hollywood following her 1932 German film Extase, Kiesler signed a contract with MGM and was given the name Hedy Lamarr by Louis B Mayer. She led a fruitful career starring opposite many of the talented and popular actors of her day, including Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable, and Jimmy Stewart.

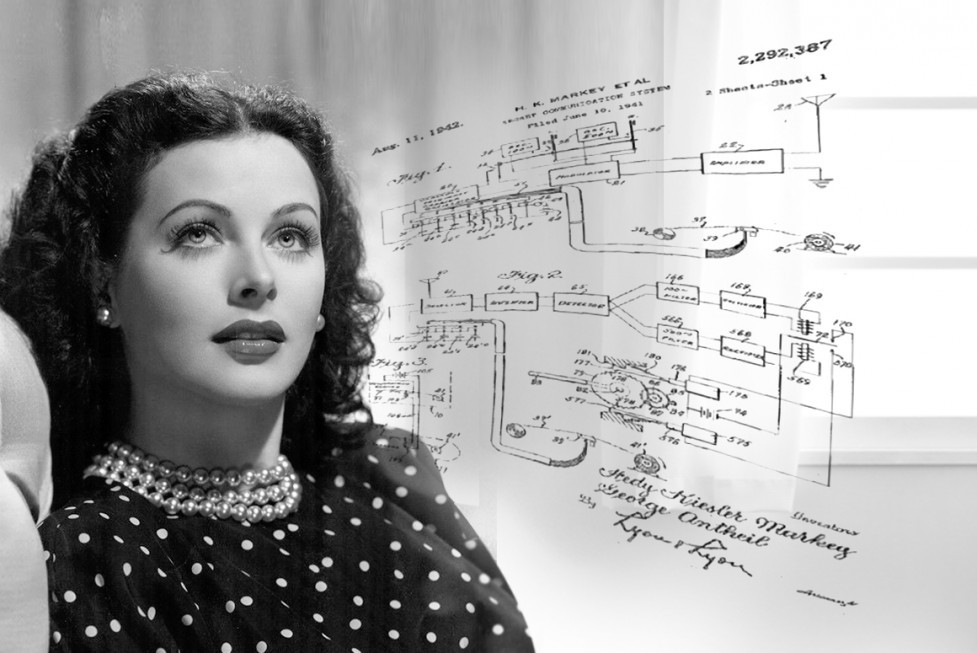

The star MGM referred to as “the most beautiful woman in the world” led an inspiring double life. In her spare time, Lamarr was a known tinker and accomplished inventor in her own right. In partnership with composer George Antheil, Lamar developed an idea to combat the tracking and jamming tactics employed by the Axis in response to the radio-controlled missiles deployed by the Allies. In a technique called “frequency hopping spread spectrum,” a pseudorandom sequence would spread the bandwidth of the message over the frequency domain, whilst constantly changing frequencies, to conceal the instructions sent to the missiles from enemy combatants. Though the technology of the time rendered the idea implausible, Lamarr went ahead and secured the patent in 1942. Upon the emergence and eventual downsizing of the transistor, Lamarr’s revolutionary idea gained relevance in both the military and personal communication fronts; her innovation became the basis of Bluetooth and WIFI devices commonly used today.

Despite her integral contributions to science, the world was not ready to accept that a woman could be both beautiful and intelligent. By Lamarr’s own admission, a glamorous woman just needs to “stand still and look stupid.” A sentiment clearly shared by military personnel as, when Lamarr approached them with her “Secret Communication System,” she was informed a greater contribution to the war effort would be made as a pinup girl. The views of the era are also embodied by the sultry, exotic women Lamarr depicted on the Silver Screen; women who could never live up to the awe and inspiration prevalent in her personal life. Regardless of mentions of Lamarr’s unusual hobby, none could see past the pretty face and juicy love life covered by the tabloids. This left Lamarr’s contributions widely unknown and unacknowledged until close to the end of her days and never fully appreciated until after her death on January 19th in 2000.

Hedy Lamarr is an icon for female scientists everywhere and an apt example of the power of on-screen presence. If she had, even once, played a character who was just as intelligent and charismatic as she, maybe the public could have seen past the many vixens and dim-witted damsels prevalent in the media to the clever, perspicacious women behind the curtains. Alas, this was not in the cards for Lamarr, but can stand as both a deterrent and encouragement for all female scientists of the significance of on-screen presence and its great potential.

Comments